If you’ve been following us recently, you’ll know we love taking Context Travel tours. We’ve taken four so far this year – two in Berlin, Walking the Berlin Wall and a Divided City – Cold War Berlin Architecture, one in Prague discovering café culture and now this one about Jewish Budapest.

All too often, when we associate the word ‘Jewish’ with any major European city or country, we convey images of the Holocaust. How many of us actually know anything about Jewish history? How Jews came to be in Europe, and how they lived – some thriving, some victims of persecutions over the century – until Nazi madness took over?

I, for starters, knew very little – just vague notions about the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, and the subsequent diaspora of the Jewish people, that ended up being scattered around Europe, Northern Africa and the rest of the Middle East.

For this reason, I was very happy to join Authentic Flavours of Jewish Budapest, a day-long tour taking us through Jewish history in the city, and concluding with lunch with a local Jewish family. Our docent Szonja was not only a member of the Budapest Jewish community, but also a Jewish history scholar, fluent in Hebrew and Yiddish.

I honestly couldn’t wish for a better guide.

Discovering Jewish Budapest history

The starting point of the tour was not chosen randomly. We met at Madach Imre Ter, a large pedestrian square not far from Deak Square, surrounded by porticos. It was a gloomy, cloudy day. Before starting the tour, Szonja gave us a quick Jewish history lesson.

I was unaware that Hungary is one of the countries with the longest-running presence of Jews – the earliest arrivals happened during the Roman Empire, 650 years before Hungarian tribes settled in the area. Over the next ten centuries, Hungarian Jews were persecuted, expelled and recalled several times by Hungary’s rulers, including the Habsburg.

We learnt that Jewish Budapest history began where we were standing – Madach Imre Ter was the former location of Orczy House, a building that is believed to be the cradle of Jewish culture and community in Pest.

In the late 18th century, after Empress Maria Theresia’s death, her son and successor Joseph II sought to improve the condition of Jews. Far from having full rights comparable to those of Christian subjects, Jews were nevertheless allowed to settle near cities, but outside the walls, after being invited by the city itself or by a noble family.

Orczy House was owned by an aristocratic Hungarian family, who invited a number of Jews to whom they leased flats, store rooms and warehouses. With time, Orczy House became the centre of the thriving Jewish community of Pest. There was a kosher café, a mikveh (ritual bath) and a synagogue that could accommodate over 500 people.

The period between the mid-18th century and early 20th century is known in Jewish history as the ‘Age of Emancipation’, the time in which Jews fought to end their discrimination and be accepted as citizens.

Over the following century, the Jewish community in Pest thrived with the arrival of Jews from other areas of Germany, Austria, Moravia and Galizia (a region of Poland/Ukraine). Inevitably, there were clashes between ‘Western’ Jews (who sought to modernise their faith and integrate with the culture of the country where they lived) and ‘Eastern’ Jews, who were closer to the Orthodox branches of their faith.

The Dohany Street Synagogue

The Jewish community in Pest became very wealthy, and it was only a matter of time before new synagogues started to be built. The first one we visited during our tour was the Dohany Street Synagogue, the largest and perhaps most beautiful of them all.

Dohany Street Synagogue was built by the Neologs, the group of Jews that was most in favour of integration and assimilation. Szonja pointed out the elements that make this synagogue a statement.

First of all, it’s huge. The twin towers on the façade (reminiscent of belltowers, Szonja added) reach 43 meters of height, dwarfing the many single-storey Pest buildings and tiny churches all around. ‘We are here, we have money – and we are no different from you’ – that’s what the Dohany Street Synagogue seems to be saying to the rest of the city.

From the outside, as well as from the inside, the building is not dissimilar from a church. There are belltowers. There are naves. There’s even an organ and a choir. And a pulpit – even though rabbis preach only twice a year. The centre of the synagogue, where functions are celebrated, is moved to the front of the building, like in Catholic churches – putting the emphasis to watching rather than participating.

But the most striking sign is outside, a Jewish inscription on two Torah-shaped tablets, right at the very top of the building, reading ‘build me a temple, and I will reside in it’.

In Judaism, the world ‘temple’ is only used to refer to the one and only, the Temple of Jerusalem. With the use of the word ‘temple’, Dohany Street Jews asserted their patriotism, their bond with Hungary.

We toured the synagogue with its luxurious interiors, and exited on the back, where a small cemetery can be found. Every single gravestone bore the year 1945 – the graves of those who died in the ghetto. Cemeteries aren’t usually located right next to synagogues, but after thousands died in the Pest ghetto liberation, they were buried in an empty plot of land next to the synagogue. After the end of the war, people started gathering to this location spontaneously, to commemorate their dead.

Right next to the cemetery is the Raoul Wallenberg Holocaust Memorial Park, named after Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish consul and saviour of thousands of Budapest Jews, who were granted documents and sheltered in buildings designated as Swedish territory. Next to it is a memorial to all the Jews that lost their life during WW2 – a weeping willow, with a name and tattoo number on each of their leaves.

In that moment, my heart felt heavy and the leaden sky seemed to overwhelm us.

We can’t escape memories of that tragedy. And the recent facts, the thousands of Syrian immigrants camping at Keleti station in that very same moment were a sad reminder that history repeats itself – and people never learn.

The Budapest Holocaust

The tour didn’t really follow chronological order – from the mid 19th century and the construction of the Dohany Street Synagogue we moved to WW2 – but after having visited Raoul Wallenberg’s memorial, it made sense.

Again, I didn’t know much about Hungary’s involvement in WW2. Hungary was allied with Germany, and Hungary’s Jews were largely protected from deportation during the first years of the war, although they were forced to live in houses marked with a yellow star, and were sent to the front as slave labour. ‘Hungary was trying to show Germany that they were good allies’ said Szonja.

Matters changed radically in 1944 when the far-right Arrow Cross party took over, endorsed by the Nazis. Raids on Yellow Star houses became more and more frequent, until a ghetto was born, for protection rather than persecution like in Rome and Warsaw.

During the short-lived Arrow Cross rule, thousands of Budapest Jews were murdered by militiamen. They were led to the banks of the Danube, that mighty, beautiful river that made my heart sing the first time I saw it. It was February 2005, and blocks of ice were floating on its deep grey waters.

When Szonja was telling us the story, I couldn’t help but wonder that in the winter of 1945, sixty years before my first visit to the city, the waters of the Danube would have been the last sight for these people – some say 10,000, some say 15,000. They were led to the riverbank, asked to remove their shoes, and then shot into the river. Floated away, like ice on the water.

All is left, now, is the Shoes on the Danube memorial, one of the most intense and poignant places I have ever seen.

The Rumbach & Kazinczy Street Synagogue

One of the places where Jews were collected to be sent to the front as slave labour (first) and to camps (then) was the Rumbach Street Synagogue, a Moorish-style synagogue built by famous Secession architect Otto Wagner at the end of the 19th century.

‘If the Dohany Street Synagogle looks like a church, this looks like a mosque’ said Szonja, as we entered the building. Rumbach Street was built as a synagogue for the Status Quo Jews of Budapest, a ‘middle way’ group that sought an alternative between the old ways of the Orthodox and the forward-thinking Neologs.

The building was indeed beautiful, but it had seen better days. Mildew was creeping on the beautifully-painted dome, and the carpet was coming off in clumps. Yet, Szonja said that only ten years ago it was a pigeon-infested ruin, after having been sold to a bank company that went bust. It has now been returned to the Jewish community, and it will probably be turned into a museum.

The last synagogue we toured was the Orthodox Synagogue a few steps away, in Kazinczy Utca. For some kind of historic irony, the Orthodox Synagogue was the last one to be built, in the first decades of the Twentieth century – just because the Orthodox community was the last one to collect enough money for a synagogue.

Inside, the Kazinczy street synagogue is perhaps the most Hungarian of them all, with pretty floral symbols reminiscent of folk art from the east of the country. The reason is that ‘Hungary’ as a concept of national identity had emerged and developed – when the Dohany street synagogue was built, the national language of Hungary was German, and the culture was still largely influenced by Vienna.

The Orthodox synagogue couldn’t have been more different to the one in Dohany Street. First of all, the leader sat in the centre, not at the far side of the room, encouraging participation of worshippers. There were no naves, and women’s balconies had screens. Plus, the synagogue was decorated floor-to-ceiling in menorah, the iconic Jewish candelabrum.

Yet, something looked odd. The menorah had 5 branches, not 7. Szonja explained that this is a reference to the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. The menorah used as decoration are imperfect, unfinished – a way to say that life won’t be perfect, until the Temple rises again.

In Judaism, there are plenty of references to the destruction of the Jerusalem temple – like stepping on glass at weddings, the custom of leaving a small section of wall unplastered, never making menorahs out of gold.

Szonja said that the 5-branched menorahs were seen as a response to the inscription on the façade of Dohany Street Synagogue ‘build me a temple, and I will reside in it’. As if the Orthodox wanted to reply ‘this is not our temple. There is only one temple’.

Once again, a Context Travel tour taught me a lot about something I knew very little. The five-branched menorahs would’ve been nothing but pretty pictures, had I visited the synagogue on my own. But this time, the tour wasn’t over – we hopped on a tram, bound to the house of a local Jewish family for a traditional lunch organised by Taste Hungary, a local tour company offering authentic food experiences.

A Jewish Lunch

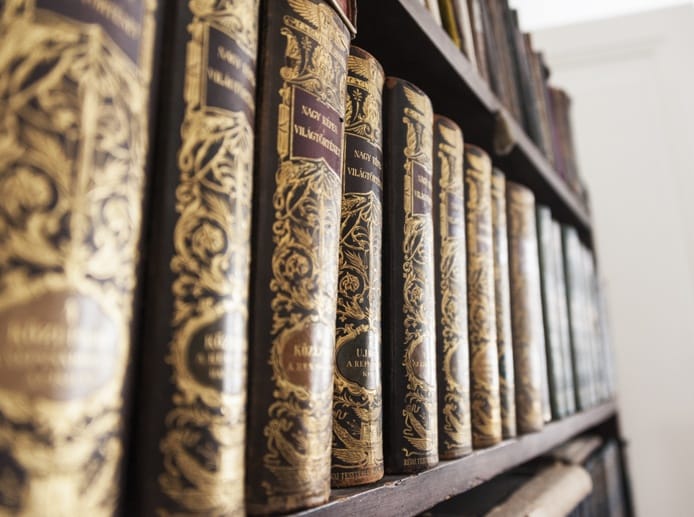

Our host Maja’s house was a true museum, with beautiful period furniture, ceiling-to-floor bookcases and cabins containing silverware and other memorabilia. Maja’s husband was a rabbi, who sadly died a few years ago. We began our lunch with a shot of palinka, typical Hungarian fruit brandy – ‘it opens your stomach’ people said. Our stomachs didn’t really need opening, as we were starving, and all the food was to die for.

We started with salmon gefilte fish, a Jewish shabbat favourite made with fish mixed with eggs and matzo balls and then poached and served cold. It’s a dish I have heard about thousands of times, but never tasted. It was slightly sweet, with raisins floating in the broth – an indication that it was made following the Galitzianer version of the recipe.

During the meal, we chatted with the other people around the table, and found out that many of them had some kind of Jewish heritage. A lady named Anna had a Jewish-born grandmother, who converted to Catholicism and never mentioned anything about having been born Jewish.

After her grandmother’s death, Anna found out the truth and immediately felt a great connection with Judaism. ‘They say Christianity is a religion of unquestioned answers. Judaism is a religion of unanswered questions’ she said.

I also learnt about taglit, the ‘birthright’ trip offered to people under 26 of Jewish descent across the world. A 10 day adventure around the country, exploring one’s roots and connection with the Holy Land. Many come back from taglit with lifelong friendships, and a deeper understanding of what it means to be Jewish.

‘Being Jewish in Israel is different’ a young lady said. ‘Here in Europe, it’s still all about the Holocaust. In Israel – somehow – they have moved on’.

Afterwards, mains were served – spiced roast duck and salted beef tongue, served with mashed aubergines, potatoes, pickles and corn on the cob.

The perfect mixture between Middle Eastern and Central European flavours – a meal that was, in a nutshell, the summary of the day we spent together. Jewish Budapest on a plate.

We were guests of Context Travel and Taste Hungary during this tour. All opinions are our own – we loved the tour and highly recommend it.

Pin it for later?

What an intense and emotional tour, especially the shoes. Thank you for sharing it with us.